Key Takeaways

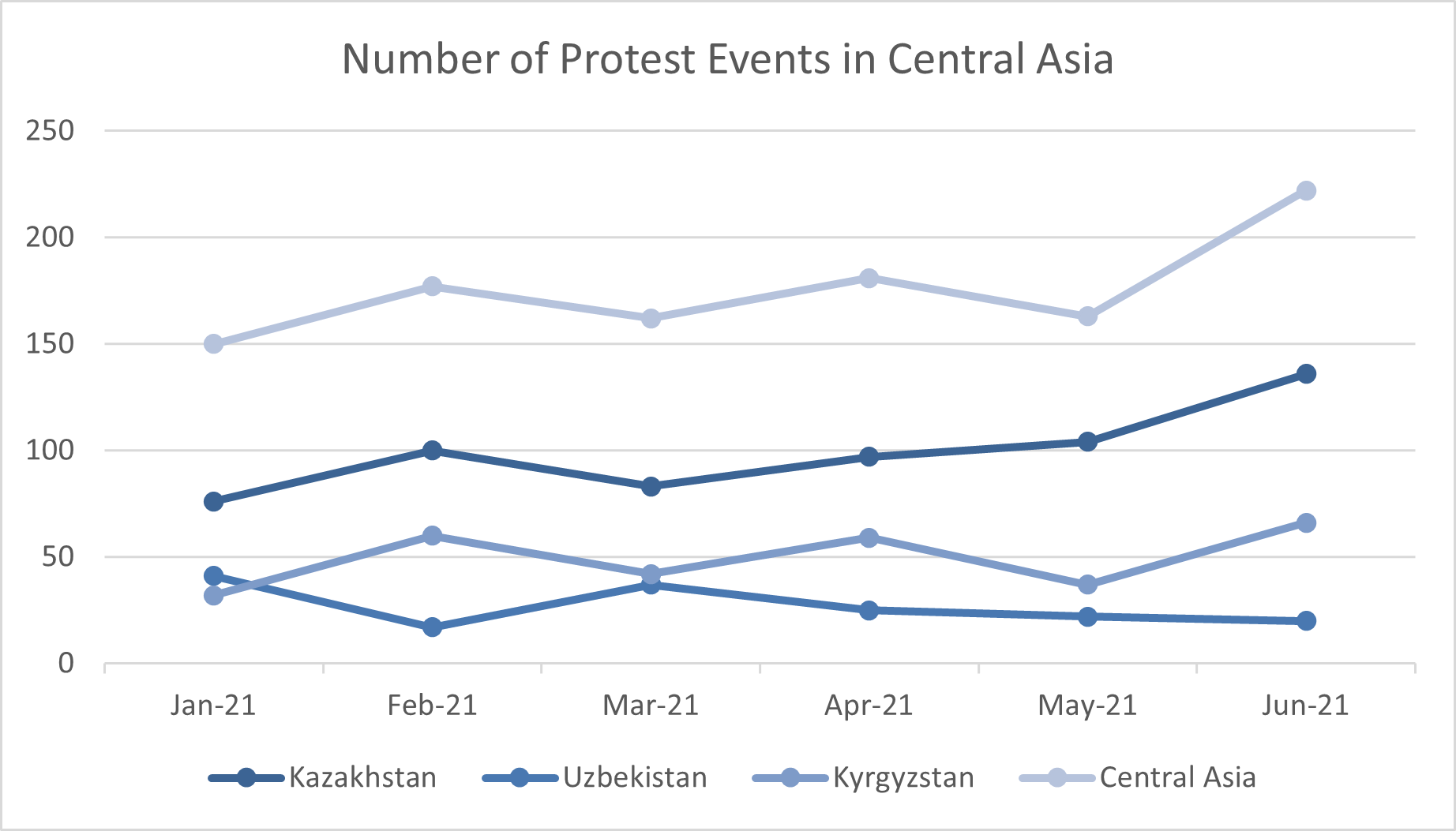

On 26 July, the Kazakh Ministry of Agriculture imposed a six-month ban on the export of certain agricultural products in a bid to relieve the growing pressure on the sector amid the worst drought seen in parts of Central Asia in over a decade. The development is the latest in a series of challenges facing the Central Asian states as other countries in the region such as Kyrgyzstan are also experiencing severe droughts and crop loss. With the state failing to provide the struggling farmers with compensation and address water-related issues, the risk of an uptick in localised protests is likely to increase in the month ahead, as demonstrated by multiple protests in Chui region in Kyrgyzstan throughout June and growing desperation from farmers in Kazakhstan.

Moreover, large-scale crop failures will inevitably heighten food insecurity across the region as growing prices of basic food staples threaten to push even more people below the poverty line. In the medium to long term, this dynamic will only compound security risks facing the region as competition over water resources alongside restive borders is likely to translate increasingly into clashes.

Growing water insecurity drives the medium to long-term risk of violent conflict along unstable regional borders

In Central Asia, access to water has been a principal driver of violent unrest and border disputes, with clashes over water access recorded on multiple occasions, most notably between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan in 2014, and more recently in April 2021. The latter incident led to a brief deployment of both countries' militaries to the border, leading to a spike in regional tensions that continue to remain heightened despite the pull back of troops in May.

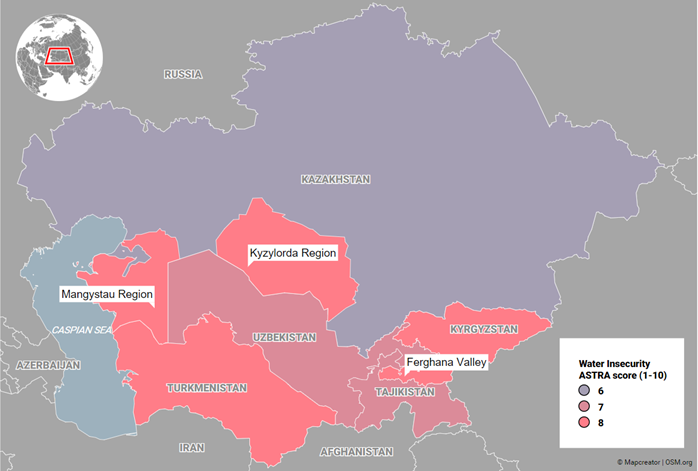

Presently, issues concerning water access rather than necessarily water availability present the main challenge and source of tensions between the Central Asian states. Upstream countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan and downstream countries such as Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan are thus often engaged in disputes over unequal water access, with the latter three states more vulnerable and thus at a higher risk of disruption to crop irrigation.

Additionally, with annual temperatures across Central Asia expected to rise, water scarcity will become a more common concern in the long term, with violent conflict over water resources highly likely to become more frequent. The restive Ferghana Valley – bordering Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan – remains particularly vulnerable to conflict due to increasing water insecurity, which is compounded by a host of other challenges including border disputes and ethnic tensions.

The deteriorating security situation in neighbouring Afghanistan to the south could still further exacerbate these tensions, with an impending refugee crisis and latent Islamist movements in the region likely to add additional pressures to already stretched water, food and security resources. As such, instability in this particular sub-region of Central Asia will worsen even further as competition over shared water resources intensifies. For further analysis on the potential impact of the NATO withdrawal from Afghanistan on Central Asia and Russia, see Sibylline Situation Update Brief 23 July.

Severe droughts drive the risk of large-scale crop failures, heightening food insecurity and an uptick in protests in the months ahead

Unprecedentedly high temperatures have been recorded across Central Asia in June and July, with temperatures in August set to remain just as high, if not even higher. The severity of the situation has already been underlined in Kazakhstan in July, where severe droughts and scorching temperatures resulted in thousands of livestock animals starving in the badly affected Mangystau and Kyzylorda regions, prompting calls for help from citizens on social media.

The crisis has already had a profound impact on local farmers, forcing them to increase their pressure and demands for much-needed assistance from the government. Subsequently, on 10 July the Kazakh Minister of Agriculture was dismissed for failing to sufficiently assist farmers and the authorities declared a state of emergency in the Aral district of Kyzylorda region on 14 July. However, the lack of compensation for farmers and allegations of the government's underreporting of the scope of the problem is highly likely to drive the risk of protests in the months ahead. Already, very similar issues have led to multiple localised demonstrations in Kyrgyzstan throughout June, with the trend only set to intensify over the coming month.

Moreover, despite the Kazakh government's vow to issue subsidies to lower the price of livestock feed by 17% – which increased by 50% according to reports in June – the promise has yet to be fulfilled. Indeed, it remains unlikely to be met in the short term, not least because the coronavirus crisis has reportedly doubled the country's budget deficit last year. Moreover, with reports last week revealing that the epidemiological situation is worsening in the region, triggering a re-tightening of some restrictions, the likelihood of the state being able to provide assistance will be furthermore undermined.

Ultimately, the situation will increase food insecurity ahead of winter, with the trend likely to endure into the long term. Already, on 26 July, the Ministry of Agriculture imposed a six-month ban on the export of certain agricultural products in a bid to relieve the growing pressure on the sector. However, the measure is merely a temporary solution and has prompted debates among crop growers, who argue that the measure comes not only too late but will also likely disrupt local supply chains and contribute to bankruptcies of local farmers.

Forecast and Implications

Countries across Central Asia are undergoing the worst drought witnessed in over a decade, underlining long-term issues over water access. Meanwhile, officials across the region appear to be downplaying the issue, with allegations of under-reporting the number of lost livestock due to the drought a particularly contentious issue, which will continue to drive local protests in the month ahead.

Moreover, in Kazakhstan, the government's promises to issue subsidies to lower feed prices for livestock is unlikely to be fulfilled in the short term, thus reinforcing the already heightened tensions between the farmers and the state. Meanwhile, a temporary ban on certain agricultural products risks exacerbating the already dire socio-economic conditions of the vast majority of small farmers, disrupting carefully cultivated agriculture supply chains over the next six months. With the state under notable pressure due to a combination of factors, such as the worsening epidemiological situation and wider regional concerns over escalating tensions in Afghanistan, state capacity will remain under notable strain for the remainder of the year.

Meanwhile, reports of volunteers stepping in to help local farmers in the absence of state support are likely to undermine public confidence in the authoritarian regime and erode government stability in the long term. However, due to the government's tight grip over all aspects of society and public institutions, including the vital security services, growing public discontent is highly unlikely to result in any revolutionary changes in the short or even medium term.

Though not as severe as in other countries, water shortages are also being felt in Uzbekistan, and have also led to crop losses and a subsequent increase in food prices. The situation has also caused disruptions to the supply of drinking water in the Samarkand region and a subsequent imposition of water rationing. The developments come just ahead of presidential elections in October, which were brought forward from December, likely due to the fact that perennial energy insecurity during the cold winter months tends to see higher levels of protest activity. Yet, with water insecurity issues also impacting Uzbekistan alongside the threat of a refugee crisis from Afghanistan, moderate protest activity ahead of the poll remains possible. However, this is highly unlikely to cause notable disruption or undermine the incumbent President Shavkat

Mirziyoyev's almost certain prospects of securing another presidential term.

Meanwhile, in the medium and long term, increased competition over water access is highly likely to translate into more frequent clashes, particularly along unstable borders in the Ferghana Valley as national priorities between the Central Asian states over water use/access and management continue to drive inter-state tensions.