The Taliban’s full takeover of Afghanistan on 15 August will have profound security implications for the country and wider region for years to come. See the end of this report for a special comment from Sibylline CEO, Justin Crump.

Key Takeaways

- The capture of Kabul on 15 August finalises the collapse of the Afghan government after weeks of rapid Taliban advances across the nation. While the speed of the process was unexpected, the government's position had become progressively vulnerable since the decision to withdraw US and NATO troops by 11 September.

- As a frenzied evacuation of foreigners from Kabul airport continues, the immediate impacts of this development are already visible. As thousands of Afghans fearing for their safety under Taliban rule head for the borders, commercial businesses – most promptly the airline industry – face a new reality of exceptionally difficult conditions.

- The Taliban's newfound 'maturity' will be tested as they attempt to govern a country of conflicting interests while under intense international scrutiny. As such, the benefits of preventing the proliferation of terrorism within their borders are clear to the new leadership. However, other jihadist networks across the wider region will almost certainly draw motivation from the Taliban’s success.

- While the coming refugee crisis will primarily impact neighbouring countries in Central Asia, the Middle East and South Asia, European nations will fear the socio-economic impacts of a repeat of the previous 2015-16 crisis.

Background

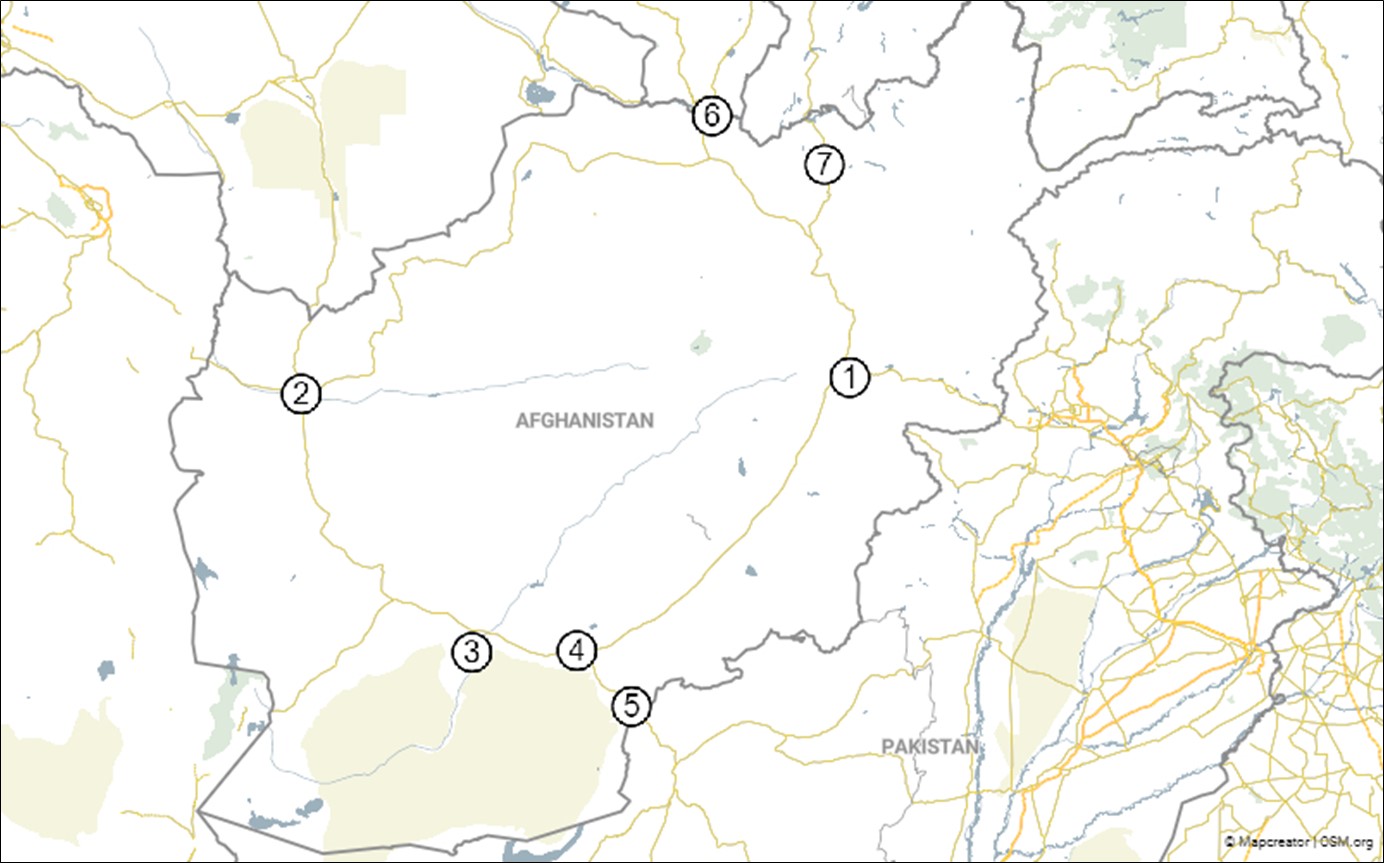

The seizure of Kabul followed the Taliban’s rapid advance across the country, as US and NATO forces near the completion of their withdrawal. Beginning in the southern province of Helmand in May, the Taliban had launched a major offensive against Afghan security forces before advancing into the mainland, steadily taking over key border crossings such as the Cham Spin-Boldak crossing between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Early August then saw the fall of provisional capitals, such as Zaranj (bordering Iran), the economic and agricultural hub Kandahar, and the important religious and tourist destination of Mazar-i-Sharif.

US President Joe Biden’s commitment earlier this year to withdraw US forces from Afghanistan by 11 September has facilitated the Taliban’s comeback. As NATO followed suit, the withdrawal of troops allowed the insurgency to gain significant advantages. As the cost of billions of dollars, Afghan forces had previously worked in sync with international partners, with foreign forces typically at the helm of operations. With this guidance removed, the operational capabilities of the Afghan forces steadily declined. Furthermore, the Taliban pursued a successful strategy of mapping the distribution of tribes and ethnic leaders or power brokers willing to negotiate, simultaneously conducting a televised military campaign that bolstered their position.

Aviation sector faces immediate impact

On 16 August, there were chaotic scenes at Kabul’s Hamid Kanzari international airport as close to 6,000 US personnel arrived to conduct evacuation operations for diplomats and personnel. Five people reportedly died as crowds rushed towards departing aircraft. Other countries such as the United Kingdom and India have also prioritised the evacuation of their diplomats, which remains difficult following the closure of Afghan airspace.

Major airlines such as British Airways, Virgin Atlantic and United Airlines have all announced the rerouting of flights to avoid Afghan airspace. For most air carriers, this will cause longer flying times and more operational costs. As events continue to unfold, this disruption will likely extend to transit aircraft.

The future of government under the Taliban

While the Taliban has a strong chain of command, it also has a relatively decentralised structure with multiple divisions. Accommodating various power brokers and local Taliban leaders into the future Emirate will be the key challenge facing the group. Despite their public line that there will be no reprisals, there are fears that the Taliban will abuse their new-found power to settle scores. However, given the number of Afghans that had links with the previous government, and the likely agreements made with power brokers to take control with little resistance, the worst excesses of this from occurring should be avoided. Overall, discussions with the US and other parties during negotiations in Qatar and Moscow suggest that the Taliban are seeking to achieve stability within an Islamic theocracy. This indicates that they are possibly more mature as a movement and group than they were during 1996-2001.

Of international concern is whether Afghanistan will once again become a breeding ground from where terrorist groups can launch attacks overseas. Those who made the decisions to pull out of Afghanistan will likely gauge the relative success of the choice by whether those fears come to fruition or not. The Taliban will be aware of this scrutiny, especially given the issues that hosting al-Qaeda caused them 20 years ago. However, the connection between al-Qaeda and the Taliban is not as strong as it was. ISIS is viewed as a threat, and potentially a rival to the Taliban.

Given these factors, it is unlikely that the Taliban will facilitate the presence of international terror groups to the same extent as their previous period in power. However, while intelligence countermeasures have improved since 9/11, the lack of a US military presence in Afghanistan will diminish their intelligence capacity significantly in the country. As a result, efforts to monitor to what extent militant groups are establishing themselves will be undermined going forward.

International reaction

The overarching hope from the international community is a desire for stability in Afghanistan. While the Taliban takeover has been widely lamented by commentators in the West, US leadership was always aware that this eventuality was a distinct possibility (even though the timescale is surprising) and would have deemed it an acceptable outcome when the decision was made to withdraw their troops.

China in particular is keen to see stability, in part given that the extremist Uighur movements were initially trained and managed out of Pakistan and Afghanistan, but mainly given the importance of routes through northern Pakistan to the Indian Ocean for future trade plans. China has given Pakistan substantial funding, including providing the money for two complete Divisions of the Frontier Corps to provide security along this route as a complement to the ongoing China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) development. The meeting of Taliban officials with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in China last month suggested that China had been preparing for this outcome, and is open to fostering workable relations.

Meanwhile, Russia has played a notable role in talks and is keen to ensure that there is no overspill of jihadism into Central Asia and thence towards Russia itself – a long-standing concern in Moscow. As with the US, both Russia and China therefore have a vested and clear interest in ensuring that the region does not become a breeding ground for further terrorism. Going forward, international governments will have to decide whether to undertake a collective boycott of the Taliban or to be pragmatic about their relations with the group.

Consequences for surrounding regions and beyond

Like much of the surrounding region, the most immediate consequence of the collapse of the Ghani government for Central Asia will be an acceleration of the impending refugee crisis. Uzbekistan and Tajikistan have already set up refugee camps at the border, anticipating a surge in the wake of the Taliban’s advance. Ethnic Uzbeks, Kyrgyzs, and Tajiks in Northern Afghanistan are especially likely to approach the borders as the prospect of Pashtun-dominated Taliban rule increases the risk of ethnic atrocities. In parallel, radicalised individuals crossing into the region, emboldened by the psychological impact of the Taliban victory, will probably revitalise latent Islamist movements across Central Asia in the coming months. [For further analysis on implications for Central Asia and Russia, see Sibylline Update Brief 23 July]. Similarly, Iran has prepared refugee camps in anticipation of more arrivals, while Pakistan is concerned that they will not have the capacity to host more Afghan refugees on top of the three million already believed to reside there.

Europe will soon also have to reckon with the coming increase in demand for safe harbour, with the increased security arrangements on eastern borders unlikely to deter those fleeing Afghanistan. European policymakers will be worried about a repeat of the refugee crisis in 2015-16, with 400,000 already believed to have fled their homes since the beginning of 2021 (according to the UNHCR). As was the case during the most recent refugee crisis, internal disputes within the EU grew significantly, with the risk of heightened ethno-religious tensions and anti-immigrant sentiment once again driving support for populist elements within domestic governments. Given the bloc is still in the process of recovering from the Covid-19 pandemic, any additional crises will be particularly unwelcome.

CEO’s Comment

The Taliban themselves appear to be surprised by quite how quickly things have changed. Although this reinforces their belief that they are on a religious mission and the strength of their conviction, consolidating territorial control requires careful footing. The most likely scenario now is that the Taliban will attempt to balance more strictly theocratic rule with a degree of conciliation sufficient to maintain power under a high degree of international scrutiny. Local outrages are nonetheless inevitable, and severe curtailments of the current pattern of life in major Afghan cities remain probable. We think the Taliban will restrict this to a level that is preferable to continued conflict and not sufficient to drive would-be warlords to react.

The international threat largely hinges on how effectively the Taliban are able to achieve this balance and consolidate power. Ongoing localised conflict, possibly caused by excessive crackdowns driving opposition, would be highly detrimental to regional stability as well as the Taliban’s ambitions for the country. A key concern is the impetus that the global jihadist movement will gain from the success of the Taliban. Broadly, al-Qaeda’s goal with 9/11 was to try and drag the US into unwinnable wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Somalia in order to encourage Muslims to flock to the jihadist cause. This latest proof that “god is on the side of the truly faithful” will almost certainly be used by a variety of groups and movements to spur recruitment and activity, regardless of tangible links to Afghanistan itself.

In the longer term, there is the prospect of resistance emerging – the civil war scenario – as the Taliban fails to accommodate hundreds of thousands of Afghans with links to the previous government, security forces and international partners. For now though, with most international and regional stakeholders showing little desire to further see destabilisation in the country, it is hard to see where local resistance movements would gain wider support and strength once the Taliban are more firmly established.

JC