Key Takeaways

- The Nigerian government has passed the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB), a major piece of legislation that multiple governments have been attempting to pass since 2008 in order to increase the ease of doing business in Nigeria's oil and gas industry.

- The legislation likely comes too late to significantly increase foreign investment in Nigeria's oil industry, with a reducing pool of capital for fossil fuel investments and Nigeria presenting a prohibitively challenging operating environment.

- Not only does the PIB not address many of these significant operational challenges largely relating to security, but it may actually exacerbate them by driving local anger over limited distribution of oil industry revenues.

Background

On 16 August, President Muhammadu Buhari signed the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) into law after it was voted through both the House of Representatives and the Senate in July. Attempts to pass reforms to the petroleum industry have been ongoing since 2008, with versions in 2009, 2012 and 2018 all defeated due to the failure to satisfy the multiple competing interests engaged in the industry from political actors to businesses and local communities. Failure to pass the bill has sustained an opaque operating environment with outdated legislation complicating taxes, licensing and driving policy uncertainty and impeding efforts to address corruption.

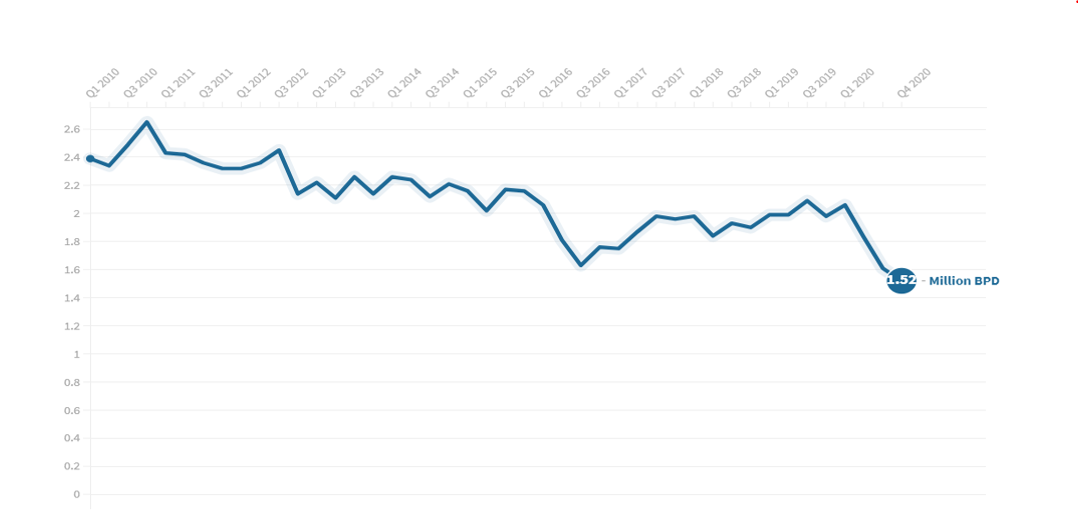

According to the government, these issues have held back as much as USD 50 billion in investment in the oil industry, which over the past decade has seen gradual declines in production. This is crucial for the Nigerian economy, as while the industry represents only 10% of GDP, it is responsible for roughly 90% of foreign currency earnings and over 50% of government revenue.

The PIB hopes to foster a more attractive operating environment for investors by separating out regulatory responsibility from the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) by establishing two regulatory agencies, reducing taxes and royalties, simplifying licensing and increasing investment in exploration.

Figure 1: Nigerian oil production, Sources – Fitch Ratings, Central Bank of Nigeria

Enduring barriers to investment will undermine profitability of energy sector despite PIB

The PIB will likely encourage some investment, but systemic challenges will mitigate its effectiveness in reversing declining interest in Nigeria's oil industry. Broadly, interest in significant investment in oil is declining globally. Western governments and their respective markets are pushing for greater action on climate change, increasing pressure for major energy companies to expand investments into renewable energy. US states and European nations are pushing ever more ambitious timetables to ban the sale of petrol-driven vehicles, while the United Kingdom is expected to pursue tougher carbon limits at the UN Climate summit in Scotland (COP26) in Glasgow starting on 31 October.

Concerns about the declining space in the market for fossil fuel goods is therefore undermining investor interest in expensive developments which may not yield profitable returns. Banks and Funds are favouring renewable energy and are actively attempting to reduce ties to the carbon economy. This trend is not only impacting new oil investments but also encouraging major companies to divest from existing projects. Chevron and Shell have sold over 20 onshore and shallow water oil blocks over the past year, with Shell indicating its intention to sell all its onshore joint-venture operations in Nigeria, citing these developments as major stumbling blocks to the company's plan to go green.

In Nigeria, the trend of declining interest in oil investments is compounded by the significant operational costs that come with major oil investments. The relationship between energy majors and local communities is often highly challenging, plagued by accusations that these companies both pollute their environment, impeding the livelihoods of farmers and fishermen, and deny them a satisfactory share of the revenues from their local resources. Not only does this drive frequent court challenges – Shell recently agreed to pay USD 111 million to the Ejama-Ebubu people for an oil spill in 1967-1970 – but combined with high rates of poverty it drives criminality and militancy among Niger Delta communities.

This presents significant threats to oil facilities and production, with militant and criminal groups repeatedly sabotaging pipelines to steal oil, a practice known as bunkering. In July, Nigerian government officials confirmed that bunkering and other such vandalism resulted in an average loss of 200,000 barrels of oil per day. This not only impacts the returns of energy majors but also increases costs by increasing pollution, inflicting clean up costs on companies and driving further disputes with local communities.

High rates of criminality also present elevated threats to local staff, with armed gangs and militant groups developing a sophisticated kidnap for ransom industry. This has on occasion resulted in attacks on oil and gas workers, and may have driven the 16 August attack in Imo state in which unidentified gunmen killed six employees of a Shell contractor. The bill does little to address this challenging operating environment and in fact may exacerbate these trends, a theme which will be discussed further below.

The PIB also does not guarantee an increase in transparency, a factor which will remain entirely dependent upon maintaining the political will to pursue anti-corruption efforts. For decades the oil industry in Nigeria has provided politicians with a source of revenue and opportunities to enrich their patronage networks driving rent seeking and high levels of corruption. While the government has stated that it is committed to addressing this trend and claims that it has been clamping down through the NNPC, there is limited evidence to support these claims.

Notably, in July Anthony Stimler, an oil trader with Glencore, admitted in a US court to paying out millions of dollars to senior government officials to secure trading contracts between 2010-2015. The NNPC has severed ties with Glencore, but not some of its partners, while no Nigerian officials or intermediaries were named in the US judgment, underlining limited willingness on the part of Nigerian authorities to seek out perpetrators. Without a significant increase in political will, commitments to increase transparency will have limited impact on governance standards in Nigeria.

The PIB plays into increasingly inflammatory rhetoric, exacerbating tensions and militancy in Southern regions

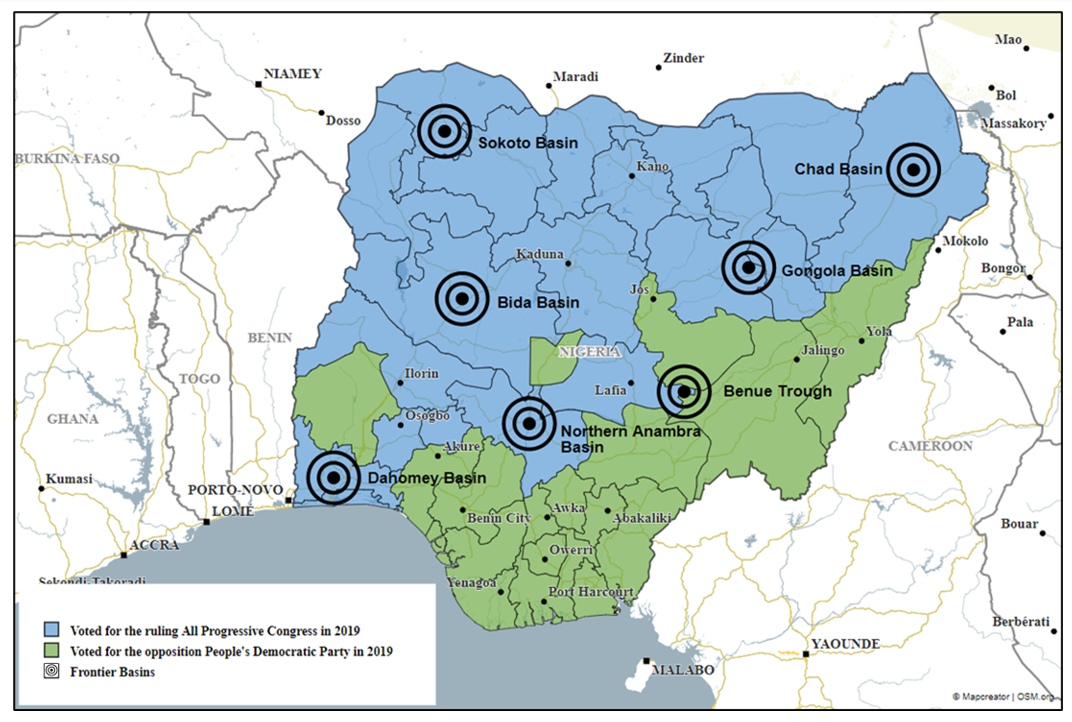

The PIB risks further enflaming tensions between local communities and both the Nigerian government and energy majors. Under the new agreement host communities will be allocated a 3% of the oil revenue; below the 5% proposed by southern politicians and well below the 10% demanded by host community representatives. Contention over this issue was further compounded by commitments to spend 30% of the NNPC's profits on oil exploration in "frontier basins" largely in the north of the country. This plays into perceptions in the south that President Muhammadu Buhari and his ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) are working in service of their northern constituency. Such investment in these northern areas appears largely unnecessary given the country already struggles to finance the extraction of its existing 37 billion barrels of oil reserves and 206 trillion cubic feet of gas.

By criticising this action and the failure to provide more investment to southern communities, local opposition politicians have boosted their popularity and are therefore increasingly catering to the ethno-centrist nature of the southern political movement. This will increase tensions around future political contests particularly should the APC choose not to select a southern politician as its candidate in the 2023 presidential election. This will elevate the threat of protests in major urban centres around polls, including major logistics and operational nodes in the petroleum industry such as Port Harcourt. Further north this trend will likely add to rising tensions between pastoral and herder communities, with Buhari accused of supporting the latter group, driving violent intercommunal clashes in Middle Belt states.

Additionally, the failure to increase host communities' access to revenues will sustain marginalisation and high rates of poverty, increasing feelings of alienation from the resources of their local area. This not only sustains hostility towards energy majors but is a key tool for the recruitment of local militant and criminal groups. The activity of such groups will sustain the currently elevated threats to local staff and assets, driving high additional costs for security, maintenance and clean ups, disrupting operations and hindering willingness to major international businesses to invest their capital in Nigeria.