Key Takeaways

- The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated the socio-economic inequities both within and between countries in the Middle East, North Africa, and Turkey (MENAT) An uneven recovery will widen these disparities as countries with high vaccination rates and rapid lifting of movement restrictions will recover at a quicker rate than those who lag.

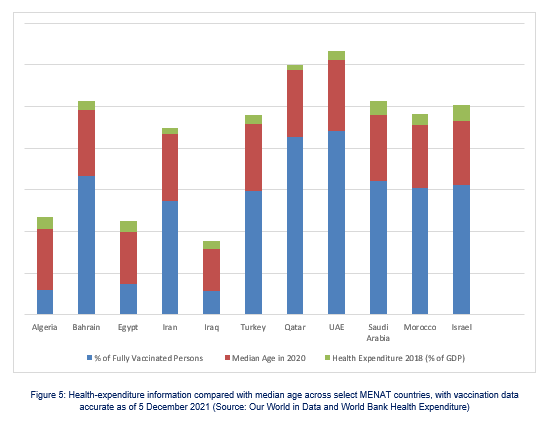

- The widening of economic inequality across the region exposes lower income countries to the effects of renewed waves of Covid-19 and deeper financial crises. Quality of healthcare is a major indicator of inequality that leaves wealthier states better equipped to face the health crisis.

- Vaccine up-take and access will be critical towards regional recovery and resilience, with richer states slow to secure donations for poorer nations. Booster doses will be essential to avoid the effects of virus mutations in the face of the Omicron variant, which has the potential to devastate economic recovery. Furthermore, high levels of vaccine hesitancy are synonymous with lower rates of government trust, with the pandemic providing an opportunity for repressive states to restrict civil freedoms.

- The pandemic has highlighted the economic vulnerability of reliance on single-income revenue streams. Economic diversification efforts, particularly amongst Gulf states, have accelerated in the past 12 months and will continue into 2022. The expansion of the non-oil private sector in alignment with ESG policies will mitigate financial shocks against renewed waves of the pandemic.

- The Covid-19 pandemic disproportionately affected vulnerable populations across the MENAT region, with socio-economic deteriorations elevating risks for displaced populations and women. Refugee populations in conflict zones will remain most vulnerable to future outbreaks.

- Finally, prolonged school closures and working-from-home mandates illustrated significant disparities in remote working capabilities across the region. Poorer nations were unable to guarantee access to internet and flexible labour arrangements, rendering affluent states better equipped to provide quality working environments. Such inequities are likely to widen educational gaps and result in negative long-term impacts on social development.

Overview

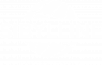

The Middle East, North Africa, and Turkey (MENAT) region was at the centre of the worst outbreaks of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, with nations such as Iran and Egypt accounting for most infections. All states were susceptible to negative effects of Covid-19, including wealthier states like the UAE who suffered significant losses in terms of tourism and aviation revenue. Nevertheless, as the pandemic persists, the uneven distribution of wealth and inequitable distribution of vaccines will widen existing socio-economic disparities within the region, as rising public grievances will continue to drive domestic instability and civil unrest.

This Special Report examines the overall impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in the MENAT region by assessing the trajectory of socio-economic recovery and identifying emerging trends in political landscapes, and what legacy such a prolonged health crisis will have on the region. Certainly, the pandemic has exposed and exacerbated existing structural fragilities in several states, but it has also tested the region's resilience and resistance in addressing economic and political shocks. The general assessment is that emergence from the pandemic, in terms of overall recovery, remains contingent upon the financial, social, and political stability of individual countries.

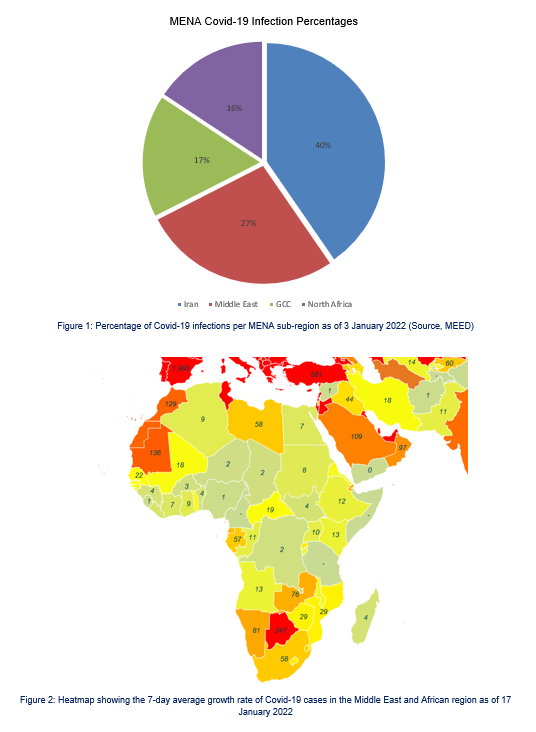

The Omicron variant has become a source of concern for MENAT with Saudi Arabia and Israel reporting locally transmitted cases of the mutation that is more transmissible than previous strains of SARS-CoV-2. After months of decline during the summer months, Jordan and Lebanon have reported the steepest increases in seven-day incidence rates as of 5 December, with the MENA region registering a total of 15,083,263 cases and 271,439 deaths registered since March 2020, excluding Turkey. As vaccines and testing apparatus will be key to mitigating the threat of the new Omicron variant, low-income countries like Yemen, Egypt, Iraq, and Tunisia will suffer from vaccine inaccessibility.

In terms of economic trends, pandemic-related oil slumps exposed the structural vulnerabilities of relying upon a unilateral source of revenue, with many states suffering from their dependence on hard-hit revenue streams, such as tourism in Lebanon and Jordan. Middle Eastern and African energy exporters will need to reassess their historically protectionist measures and bolster foreign investor confidence with ESG-aligned policies to build resilience against future shocks. Ultimately, the post-pandemic environment in the MENAT region will further divide high and lower-income countries, as varying levels of state resilience will widen socio-economic inequities and exacerbate political insecurities. Renewed waves of infection and the possible re-implementation of lockdown measures in 2022 will have catastrophic financial and social consequences, as depleted healthcare systems and chronic pandemic fatigue threaten to cause irreversible shocks and cause major operational disruptions.

The Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated existing structural deficiencies and financial weaknesses across the region

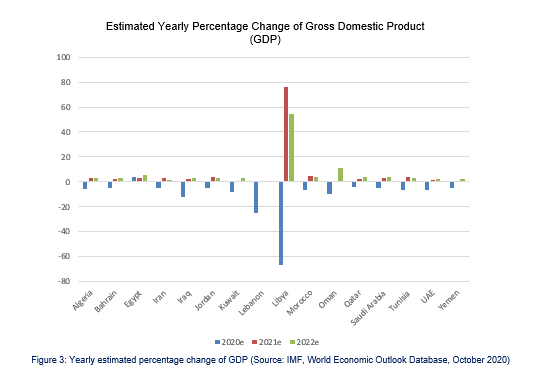

Every corner of the MENAT region felt the fiscal challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic, however prospects of recovery and resilience to economic shocks vary considerably. Public debt and state budget deficits rose to unprecedented levels throughout 2020 and threaten to have significant knock-on effects on fiscal balances. Although the World Bank estimates that MENA's GDP will grow by 2.8% by the start of 2022, the region suffered a collective loss of USD 200 billion since the beginning of the pandemic, with economic recovery likely to be uneven and expose structural fragilities.

Decades of poor economic governance and short-sighted fiscal policies rendered some governments incapable of supporting businesses

The pandemic brought the MENAT region's monetary imbalances to the forefront, with uneven recovery, both within and between states, likely to compound fiscal challenges and impact investment opportunities. Whilst richer oil-dependent states have leveraged the last 20 months to accelerate the economic diversification of their revenue streams away from hydrocarbons, lower income states have struggled to adapt to the increasingly volatile economic market. Collapsed oil prices, disrupted supply chains, labour remittances and shrinking external demand forced developing countries to boost public spending caps and extend borrowing mechanisms, leaving them in a protracted state of recession.

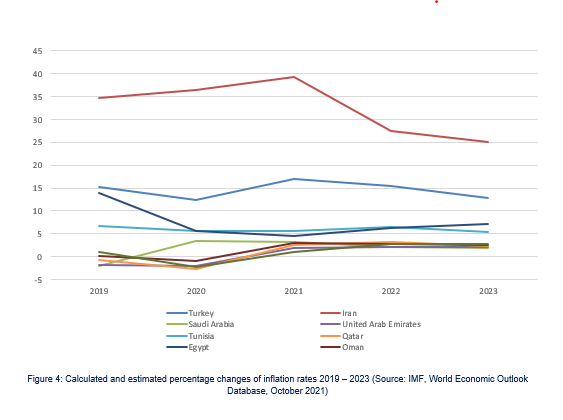

The economic downfalls associated with the Covid-19 pandemic prompted a region-wide rise in public debt, inflation, job losses and high unemployment rates, particularly amongst the youth. While the root-causes of economic insecurities existed before the pandemic, disruption to global markets and the extended closures of non-essential businesses exacerbated public spending and liquidity levels. Oman and Tunisia suffered under already high levels of public debt in 2019, with the pandemic sustaining the risk of tax hikes and spending cuts amongst populations that have already experienced significant slashes to incomes.

In many regards, decades of poor economic governance and fiscal policies exacerbated financial fallout from the pandemic. For instance, Turkey's inflation rate rose for the fifth consecutive month in November 2021 nearing 20% and the lira weakened by a total of 35% in the same year. This is a clear consequence of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's short-sighted monetary policy designed to stimulate the Turkish economy during the Covid-19 pandemic. Erdogan's economic strategy threatens to negatively impact local businesses amid severe currency depreciation and rising consumer costs, with further economic slides creating an unstable and unattractive investment environment.

Furthermore, the capability of governments in implementing state-sponsored financial support packages correlated directly to fiscal rebounds and retaining market stability. For instance, the Bank of Israel targeted households and organisations by reducing their regulatory capital requirement by 1%, increasing overdraft credit capabilities and deferring loan repayments for individuals financially impacted by Covid-19 restrictions. Whereas lower-income countries reliant on remittances, including Iraq and Lebanon, did not have the infrastructure or fiscal capabilities to implement such initiatives. Whilst the World Bank provided a financial bursary of USD 100 million to up-scale Iraq's health sector and introduce a cash transfer scheme, the Iraqi dinar weakened, and the government failed to enact reforms to address ongoing cash flow issues. Operational disruptions and business closures are now commonplace across Iraq, rendering many populations without stable income.

The pandemic exposed the economic risks associated with unilateral revenue streams and the need for sectoral expansion

Protracted movement restrictions and the closure of most-nonessential sectors prompted a major decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) and global economic activity, as investors became increasingly risk-adverse in an uncertain environment. The collapse in oil demand revealed severe structural issues that prompted hydrocarbon-dependent Gulf states, including Bahrain, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia, to accelerate policies to expand their largely underdeveloped private sectors. Though efforts to attract long-term investment opportunities and mitigate economic shocks associated with single-income revenue streams were underway prior to 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic fast-tracked many of these initiatives with a sense of urgency.

Considering oil slumps, economic diversification and expansion of the non-oil private sector has characterised monetary policies and structural reforms amongst Gulf states in the last two years. Investment in human capital and privatisation opportunities aimed to bolster employment for both local and foreign candidates, with Saudi Arabia and the UAE shifting traditions to accommodate expatriate interests. For instance, from 1 January 2022, federal and government departments across the UAE will shift the working week from Monday through to Thursday, with a half day on Friday. The private sector is likely to follow suit, with businesses likely amending their working pattern to better align with real-time trading and communication-based transactions.

Nevertheless, whilst Gulf states have largely sought to bolster economic recovery via the expansion of their private sector, Algeria has maintained damaging protectionist measures in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Though the country is equally dependent upon hydrocarbon exports, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune illustrated his reluctance to shift away from protectionist policies and has instead called to cut public spending considering the collapse in oil demand. Not only will this deepen Algeria's fiscal imbalances and increase public debt, but the government's monetary policies also threaten to exacerbate rising anti-government sentiments despite Tebboune's heavy crackdown on protest movements.

Furthermore, while richer states have been able to rely upon hefty reserves and fiscal resilience, poorer states who depend on third-party remittances from countries such as Saudi Arabia have suffered under restrictions and weak state institutions. MENAT states who are reliant on the tourism industry experienced dramatic economic downturns, with continuous international travel restrictions and fragile epidemiological environments due to new variants likely to stall the resumption of tourism even in 2022. As a result, local businesses in Morocco, Egypt and Tunisia are at the epicentre of economic losses, with financial contractions pushing unemployment and inflation figures, as youth unemployment reached up to 42.8% in Tunisia during Q3 in 2021. Protracted levels of youth unemployment are likely to present numerous challenges in terms of social development, with persistent gaps in the labour market likely to sustain higher poverty levels, crime rates and an unstable operational environment.

Exposing the state of different standards of healthcare in the region

Prior to the pandemic, developing countries (e.g., Iraq and Tunisia) suffered from overstretched healthcare systems due to lack of staff and poorly funded facilities. Decades of austerity measures and insufficient financial backing rendered these sectors incapable of coping with a pandemic. Contrastingly, over the past two decades, the UAE and Saudi Arabia have invested heavily in public healthcare systems, with the latter allocating up to 4.7% of annual GDP, which is crucial for increasing resiliency during a prolonged health crisis.

Conflict zones and fragile states in the MENAT region remain susceptible to recurring outbreaks of Covid-19 infections due to critically weak infrastructure. Poor access to treatments and regular testing has left states including Yemen, Iraq, and Lebanon unable to curb the spread of the virus, sustaining the risk of new mutations and vaccine-resistant variants to survive and expand. These zones will remain wholly reliant on the provision of third-party financing and international aid to mitigate future Covid-19 infections, despite overstretched multilateral institutions struggling to repeatedly finance crises.

Richer states such as the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Qatar have the best health facilities across the region rendering them capable to withstand the major impacts of the pandemic. Pharmaceutical development amongst Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states has also equated to higher levels of protection. Additionally, the UAE will become the first Arab country to produce a Covid-19 vaccine from Chinese pharmaceutical giant Sinopharm, which will result in higher levels of vaccine accessibility and distribution.

The Covid-19 pandemic provided the legal and regulatory means for governments to restrict civil freedoms

The Covid-19 pandemic provided an opportunity for governments in the region to impose increasingly repressive regimes, with the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres noting in April 2020 that the phenomenon could "provide a pretext to adopt repressive measures for purposes unrelated to the pandemic". Over the past 20 months, normalising the use of emergency measures to curb the spread of infection has established an environment which enables significant democratic backsliding, particularly amongst states that have previously transitioned from an autocracy to democracy in the last decade.

Many countries across the region were quick to implement or extend nationwide state of emergency legislations, often interpreted as a mechanism to restrict social freedoms and expand authoritarian tendencies. Whilst states such as Saudi Arabia issued harsh penalties, including fines and prison sentences for non-compliance, countries such as Algeria and Tunisia utilised curfews and quarantine measures to prevent the mobilisation of anti-government protests. The implementation of repressive measures benefited leaders facing rising levels of public dissent towards the end of 2019, with the pandemic providing the legal means to ban demonstrations and impose harsh penalties. Tunisian police forces utilised exceptional force to break up several "anti-establishment" protests in February and July 2021, whilst Lebanese police convicted 35 protestors of terrorism for their involvement in anti-lockdown demonstrations that took place throughout Nour Square in Tripoli in January last year.

As civil society organisations and activists reported major constraints on their freedoms of expression, regional governments framed stringent pandemic-related regulations as attempts to suppress the spread of Covid-19 misinformation and fake news. The shift of the world online paralleled with the enhancing of online surveillance capabilities and the shutdown of internet access to disrupt the mobilisation of protest movements. In March 2021, the Jordanian government thwarted Facebook live services to control demonstrations following the Al-Salt hospital incident, where Covid-19 patients died due to the lack of oxygen supplies. Similarly, the Iranian government blocked Signal, a messaging app which gained popularity following concerns surrounding the state surveillance of WhatsApp, on 25 January 2021. The subsequent increase of state surveillance has significant implications for businesses, with the lack of transparency and censorship creating an unattractive environment for personnel and a loss of civil liberties. Internet blackouts can also cause considerable disruption to the fluidity of operations and maintaining communication with staff.

Moreover, despite being the epicentre of Covid-19 infections in the MENAT region, Iran's government has repeatedly utilised the pandemic to further geopolitical objectives and exert domestic control. Having recently emerged from their fifth wave, Iran continues to record one of the highest incidence and death rates, with delayed state intervention, poor compliance and lagging vaccination up-take responsible for the spread of the virus. Mismanagement and false information have been symbolic of the country's strategic response to the health crisis, with skewed medical advice and inconsistent figures severely underestimating the true epidemiological landscape of the country. Furthermore, Iran's hard lined and ultraconservative President Ebrahim Raisi has exploited the health crisis to bolster anti-Western sentiments, spread conspiracy theories and state-sponsored media campaigns....