General Overview

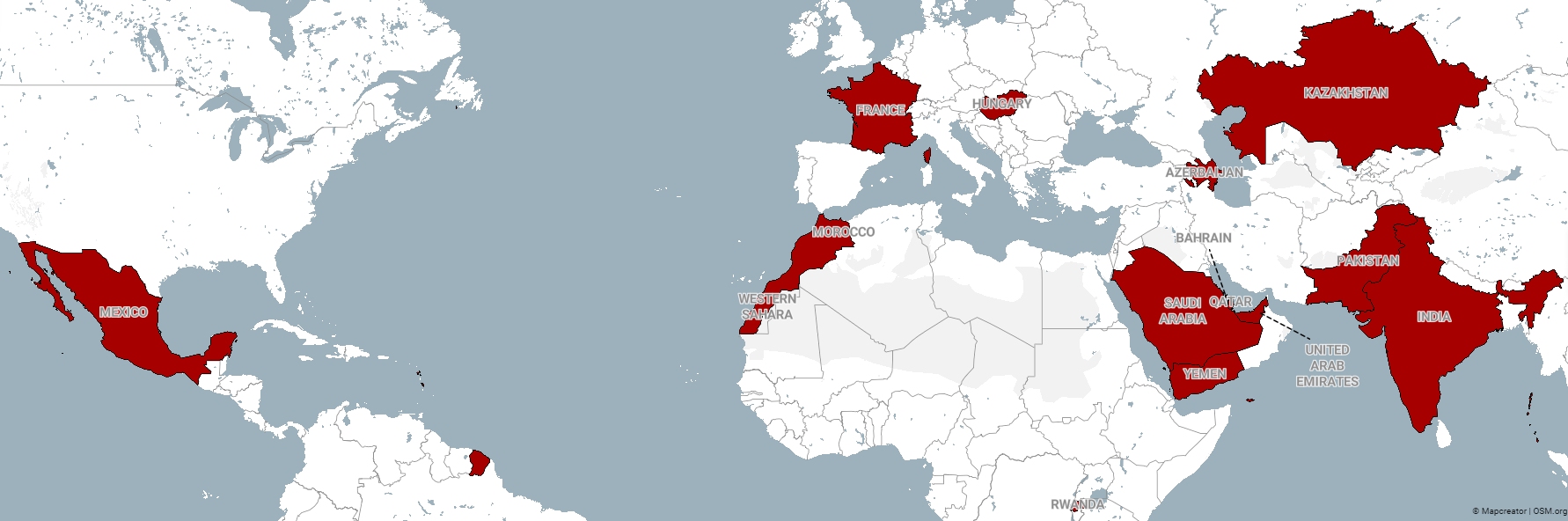

On 18 July, an investigation conducted by a consortium of international news organisations and human rights groups, including the Washington Post, Le Monde and Amnesty International, secured access to a leaked list of more than 50,000 phone numbers targeted for surveillance with Pegasus, a spyware tool developed by Israeli surveillance firm NSO Group. The list of phone numbers contains devices in use across Asia Pacific, Europe, Eurasia, and the Middle East/North Africa. Although the list does not name the clients of NSO Group who purchased Pegasus spyware for use, phone numbers identified to date include opposition politicians, political dissidents, security and military operatives, independent media, students and activists from across the globe, raising fears that state actors may have employed the software illegally.

The Pegasus scandal will potentially undermine businesses environment in India and could drive up India-Pakistan tensions

In India, over 140 individuals including leading journalists, lawyers, government ministers, and opposition party members have appeared on the Pegasus list. Some of these individuals include opposition Congress Party head Rahul Gandhi and Ashok Lavasa, the former election commissioner of India who had accused Prime Minister Narendra Modi of violating the model code of conduct before the 2019 general election. In the wake of this discovery, opposition party members have accused Modi of “treason”, alleging that his government purchased and used the Pegasus spyware against opposition members, and have demanded the resignation of Home Minister Amit Shah. The Supreme Court has begun hearing petitions that demand the government initiate a probe into the scandal from 4 August, although it is unlikely the Modi government will face significant repercussions.

The Pegasus scandal, coupled with ongoing farmers' demonstrations and civil unrest related to the Covid-19 pandemic, does hold the potential to instigate wider unrest across India. More specifically, growing public discontent with the Modi government's ongoing crackdown on dissident voices may compound new revelations that the government has subjected political opposition members to surveillance. An increasing number of students, comedians and activists have been arrested under anti-national and terrorism laws since the Modi government came to power in 2014, with the recent death in custody of activist Stan Swamy sparking protests in several cities. Additionally, the Modi government has been criticised by civil liberties groups internationally for tightening its internet regulatory laws in a perceived attempt to curtail independent media. Most recently, Delhi demanded earlier this year that social media platforms Facebook and Twitter take down hundreds of posts, divulge sensitive user information and submit to a regulatory regime and threatened the firms' executives with potential jail terms in the case of noncompliance.

The Pegasus scandal, therefore, further highlights operational risks posed to firms – particularly those unaligned ideologically or politically with the Modi government – operating in India, with little clear recourse available to individuals or entities targeted by government-sponsored surveillance. Whilst interruptions to business operations due to public protests remains a potentiality, firms operating in India will have to assess the risk that their operations may be subject to state-sponsored surveillance. While it is unlikely this scandal will result in any immediate government instability, it will likely be an important issue over the coming years as India heads into its next general election in 2024.

Elsewhere, in Pakistan, Prime Minister Imran Khan has been named as an alleged target of the Pegasus spyware, and it is currently understood other Pakistani government officials are also present on the Pegasus list. Pakistani authorities have said that they will investigate if the alleged surveillance attempts originated from India, terming these attempts “cyber attacks”. If the allegations of the Pakistani government turn out to be merited, India-Pakistan bilateral relations will be negatively impacted, heightening the risk of cross-border shelling or drone attacks along the highly militarised India-Pakistan border in coming months. While Pakistan has so far opted to call on the United Nations to “thoroughly investigate the matter, bring the facts to light, and hold the Indian perpetrators to account”, there will, nevertheless, remain a latent threat of Islamabad launching some form of retaliation – cyber or otherwise – if the UN-led investigation does not produce a result that is considered satisfactory to the Pakistani government.

Fears over phone surveillance allegations spark investigations in France and Hungary, but little recourse available for affected individuals in Eurasia

In Eurasia, it is understood that the number of individuals affected by the Pegasus scandal may number in the hundreds, with journalists, activists and opposition politicians in Azerbaijan and oligarchs and governmental officials in Kazakhstan confirmed at present to have been subjected to surveillance. Several affected individuals have claimed that government security agencies were behind the alleged spying efforts. US-based NGO Freedom House has suggested that some of the 'most powerful' oligarchs in Kazakhstan, including high-profile opposition members living in exile, were likely targeted by Kazakh security agencies at the behest of President Nursultan Nazarbayev. However, while these revelations are likely to increase opposition activity in both Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan against the government, it is unlikely that the Pegasus scandal will have a meaningful impact on human rights norms and media freedoms in the region, with few real remedies available to groups or individuals affected by alleged spying.

In Europe, the advent of the Pegasus surveillance scandal has most visibly been seen in allegations made that Pegasus spyware was used to monitor French President Emmanuel Macron, as well as at least 15 current and former members of the French government. Moreover, an unspecified number of French journalists and politicians are also believed to have been monitored from 2019. French national newspaper Le Monde found that a Moroccan intelligence agency had registered President Macron's phone alongside those of other French governmental staff on a 'watch list' for potential spyware targeting in 2019. Although an NSO official has stated to Israeli news that the French president was never a direct target, the revelations have heightened the French government and security services' scrutiny of France's cyber capabilities.

Further afield, this incident has also instigated an investigation into the allegations that Moroccan intelligence services could have spied on French politicians, governmental ministers and journalists. The French media firms targeted are believed to include major outlets including Agence France-Presse, France 24, Mediapart and Le Monde. As a result, regional tensions with Morocco are expected to increase in the coming weeks as the investigations continue, with serious questions raised over the extent to which NSO Group was aware of the targets and methodology employed by the clients to whom it sold the spyware.

Elsewhere in Europe, according to a joint international investigation coordinated by the French non-profit organisation Forbidden Stories, a wide range of individuals in Hungary in particular were targeted with the Pegasus spyware. According to leaked documents containing over 300 Hungarian telephone numbers, potential targets of the spyware include Zoltan Varga, a wealthy investor and owner of the Central Media Group operating one of the last remaining independent outlets in Hungary; at least 10 lawyers; an economist; a former state secretary of the Orbán government who was in charge of the Paks II nuclear plant expansion project awarded to Russia; a Canadian-Belgian PhD student at the expelled Central European University; and a regional mayor in longstanding opposition to the Orbán government.

The Pegasus revelations not only raise concerns about human rights and lax legislative frameworks for surveillance in Hungary but also point to potential future operational risks for international or domestic businesses that might be perceived as ideologically opposed to the Hungarian government. While the findings of the Forbidden Stories investigation indicate that Hungarian surveillance through Pegasus was mostly domestic in scope, potential surveillance of foreign businessmen and lawyers could pose significant security risks to international business stakeholders, including foreign nationals, operating in Hungary. Moreover, this could potentially increase the risk of regional tensions between Hungary and the European Union, and could negatively impact Hungary’s foreign relations with countries that are considered to have good working relations with the Orbán government, including Germany and Israel.

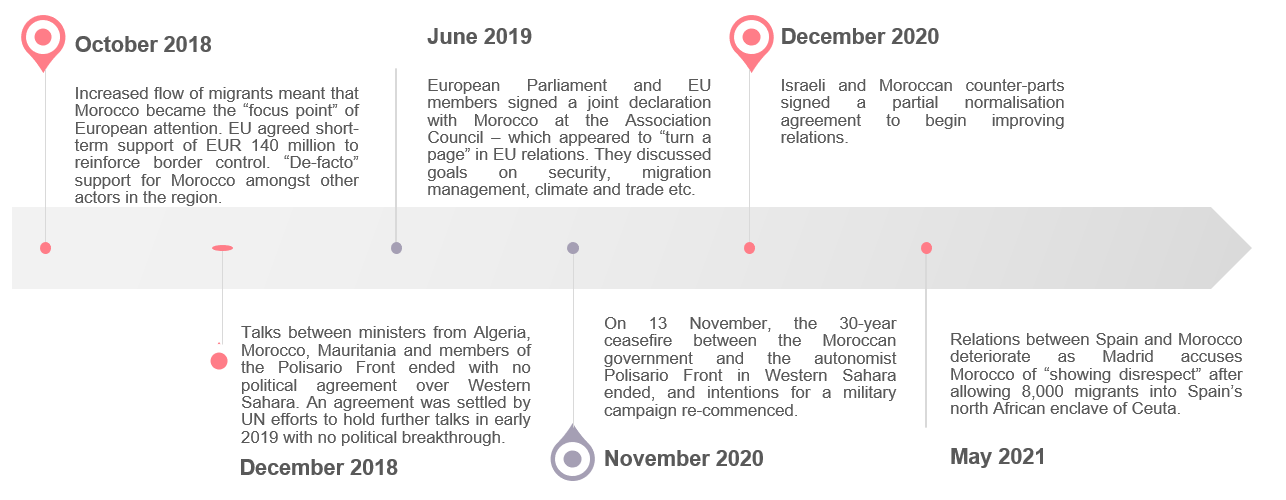

Spying allegations escalate Morocco’s tensions with the EU and will reflect negatively on recent Israel relations

In addition to accusations of bugging the phones of French President Macron, the Moroccan government has also been accused of monitoring thousands of individuals based in Algeria through the Pegasus spyware. The revelation that Morocco’s security services used Israeli Pegasus spyware only months after signing a partial normalisation agreement with Israel could shine a negative light on the agreement and therefore Israeli efforts to sign further such accords with other Arab states. Notably, there has been some speculation that the governments of Morocco, Bahrain and the UAE, the three Arab states to have normalised ties with Israel, would seek to boost defence and technology cooperation with Israel as a priority given Israel’s expertise and well-developed sectors. Nonetheless, the sharing of such technology raises reputational and security concerns not only for Israel but also for governments of the likes of the UAE and Morocco who may use such technology against own populations, especially considering the elevated risk of unrest in Morocco and Bahrain. Morocco in particular has become increasingly intolerant of dissent in recent years amidst challenges including high youth unemployment and bouts of socio-economically driven unrest, such as teachers protests. Morocco is known for targeting journalists and activists, frequently reporting their arrests.

In a similar vein, the recent disclosure will raise concerns for businesses and entities that could be perceived as targets for a government, such as Morocco’s, which is increasingly hostile to opposition and criticism, particularly over its claim to sovereignty over Western Sahara. This is currently a highly sensitive issue for Rabat which has already flared tensions with European partners such as Spain and Germany. Notably, a recent spat resulted in Morocco allowing thousands of migrants to enter the Spanish enclave of Ceuta in May in response to Spain’s hosting of the leader of Western Sahara’s pro-independence Polisario Front.

As a result, the allegations against the Moroccan government are the latest episode of escalating tensions between Morocco and another European partner. France is a key ally of Morocco, with close business ties and cooperation in the fight against Islamist terrorism. This development, therefore, underscores Rabat’s current anxieties as it seeks to consolidate its claim over Western Sahara, risking good relations with some of its closest partners. The alleged targeting of French officials crucially comes ahead of a European Court of Justice ruling, likely in September, on the EU-Moroccan Association Agreement’s application to disputed Western Sahara. Rabat will therefore seek to maintain pressure on European actors in the coming weeks.

Growing scrutiny of Israel's surveillance industry indicates Pegasus scandal is not an isolated incident, underlining deteriorating data security trends

The emerging details of the Pegasus scandal are the latest in a series of alleged human rights violations involving NSO Group's software. However, this is the most notable incident involving NSO Group's spyware technology since WhatsApp filed a lawsuit in October 2019 against the Israeli firm for illegally helping several national governments compromise the devices of more than 100 journalists, human rights activists, and other individuals of interest worldwide. WhatsApp's Chief Executive, Will Cathcart, revealed in the wake of the Pegasus report that nearly 1,400 individuals, including those holding "high national security positions who are allies of the US", were targeted by spyware developed by NSO Group during the 2019 attack. Cathcart also went on to say that he believes there are numerous "parallels" between the 2019 espionage activity launched against his firm and the most recent Pegasus campaign. More specifically, the WhatsApp chief executive said that "many of the targets in the WhatsApp case had no business being under surveillance in any way, shape, or form" and that the targeting appears to conflict with NSO's licensing agreement that its software should only be used for tracking terrorists and major criminals.

More generally, these accusations are also in line with the growing number of scandals that have implicated Israeli security firms in recent years. For example, fellow Israeli firm Toka, which also only sells to governments and security agencies, has been accused of human rights violations by providing "spy tools for whatever device its clients require". Originally founded by Ehud Barak, former Israeli Prime Minister and former head of the Israeli military intelligence directorate Aman, the company works with, and offers its software almost exclusively to, governments that have strong connections with Tel Aviv.

Much like with Pegasus, Toka's hacking equipment is classified as a "lawful intercept" product that has the ability to target any device connected to the internet, including smartphones and laptops. However, Israeli security firms' focus on developing custom cyber espionage tools and the recent string of illegal espionage activity, such as Pegasus, has raised concerns amongst human rights advocates over these companies' inability to effectively control how government utilises their software. This distress has been particularly palpable throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, which has seen a number of governments strengthen their cyber surveillance capabilities in an effort to curb the spread of the virus (see Sibylline Cyber Situation Update Brief - 7 April 2020 for further analysis). While there is a high likelihood of human/privacy rights activists highlighting the Pegasus revelations to call for regulatory constraints to be placed on these security firms, it is unlikely that such calls will significantly alter NSO Group or Toka's business model/operations.

Forecast and Implications

Overall, while the discovery of the Pegasus spyware campaign indicates a worsening trend of data security and privacy rights across several jurisdictions, a myriad of more regional implications are also apparent. In the case of the Asia-Pacific region, the Modi administration's surveillance activity will further prolong tensions between India and Pakistan and heighten the risk of tit-for-tat border incidents in the coming months. Similarly, the Pegasus scandal will also raise regional tensions between Hungary and the EU, as well as France and Morocco. While the risk of domestic unrest emerging as a result of these revelations in the aforementioned regions is likely to remain low, the Pegasus scandal nevertheless underlines certain actors' growing willingness to utilise extra-legal measures to target independent voices in the media, academia, the judiciary, and the business sector.

More broadly, with concerns such as international terrorism, single-issue-motivated activism and the spread of more infectious Covid-19 virus variants, there is a high probability of national governments increasing their reliance on invasive surveillance technology to either pre-emptively deal with emerging security threats and/or mitigate the risk of resurgence of Coronavirus infections. Good-faith use of similar surveillance technology in this manner will be negatively impacted by the adverse media attention generated by the Pegasus scandal. Furthermore, there is also a heightened risk that independent media and political opposition members in Central and Eastern Europe, specific regions of Asia Pacific and the Middle East will disproportionately be targeted by state-sponsored surveillance tools. There is also a high likelihood that private security firms will come under increasing regulatory scrutiny in coming months, particularly in the EU and the US. This tightened scrutiny will pose a long-term reputational risk to not only the security firms themselves but also any entities that are perceived to be either making use of and/or enabling their services, presenting a more complex risk environment to businesses and national agencies wishing to employ surveillance software in good faith to protect against increasingly diverse security threats.